Wearables

Wearable wonderland:

how tech is tackling Covid-19

From symptom signalling and social distancing to contact tracing and controlling face-touching, wearable devices are being harnessed in all sorts of novel fashions to help combat the Covid-19 pandemic. Chloe Kent rounds up the best and brightest.

F

or many life sciences companies, Covid-19 has provided a perverse boost for business. Despite a worldwide recession, companies that manufacture products such as ventilators and other breathing support devices have found that the pandemic has triggered a huge increase in the demand for their product.

The same is true for wearable device manufacturers. Wearables were already on the up before the pandemic began, but research by GlobalData estimates that the market is now on track to increase from being worth nearly $27bn (£21bn) in 2019 to a whopping $64bn by 2024.

This is due to a surge in the number of people using wearable devices to monitor themselves for Covid-19 symptoms or, in some jurisdictions, to implement contact tracing and social distancing. Medical Technology takes a closer look at some of the most compelling projects emerging from this space.

Oura: a smart ring to detect early Covid-19 symptoms

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), are using the Oura smart ring to test whether tracking data such as body temperature, heart rate and respiration may enable people to detect the early onset of Covid-19, before they notice they’re unwell.

The data collected by the Oura wearable will be combined with responses to daily symptom surveys, to build an algorithm that can help UCSF identify patterns of Covid-19 onset, progression and recovery. The research team are studying a group of more than 2,000 frontline healthcare workers as well as members of the general population.

Image: Oura

Doctors, nurses and other clinical staff who are in daily contact with sick patients who may have Covid-19 at UCSF campuses will receive Oura rings. The study is also open to all Oura ring users, who can likewise contribute to the data pool.

The Oura ring has a number of different sensors, including infrared LEDs, an accelerometer, gyroscope and three temperature sensors, which it can use to track various vital signs.

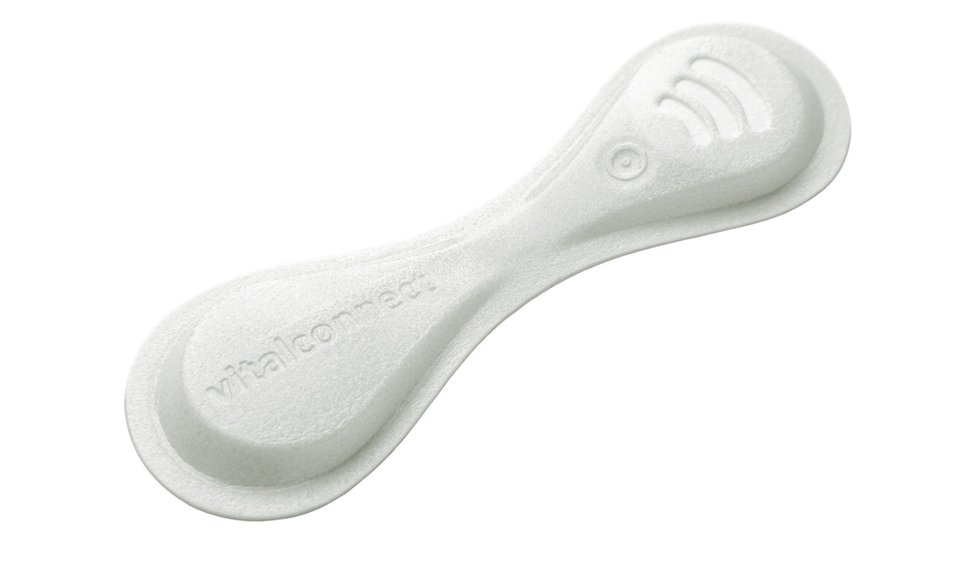

VitalPatch: monitoring Covid-19 patient drug response

In May, VitalConnect obtained Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its VitalPatch wearable biosensor, which can now be used to monitor heart-related side effects to drug treatments for Covid-19.

As different drugs are used to try and treat patients seriously afflicted by the disease, the VitalPatch biosensor can be used to detect changes in the patient’s QT interval, a measurement made on an electrocardiogram to assess some of the electrical properties of the heart.

Image: VitalConnect

Drugs such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, which have been used in attempts to treat Covid-19, can cause prolonged QT intervals for patients and may also lead to arrhythmias.

Using the VitalPatch, clinicians can remotely and continuously monitor the hearts of seriously ill patients to see if they are experiencing a prolonged QT interval as a result of their treatment. This can allow for the creation of more personalised and appropriate treatment plans.

The VitalPatch wearable can measure 11 physiological vitals overall, including temperature, heart rate and blood oxygen saturation levels.

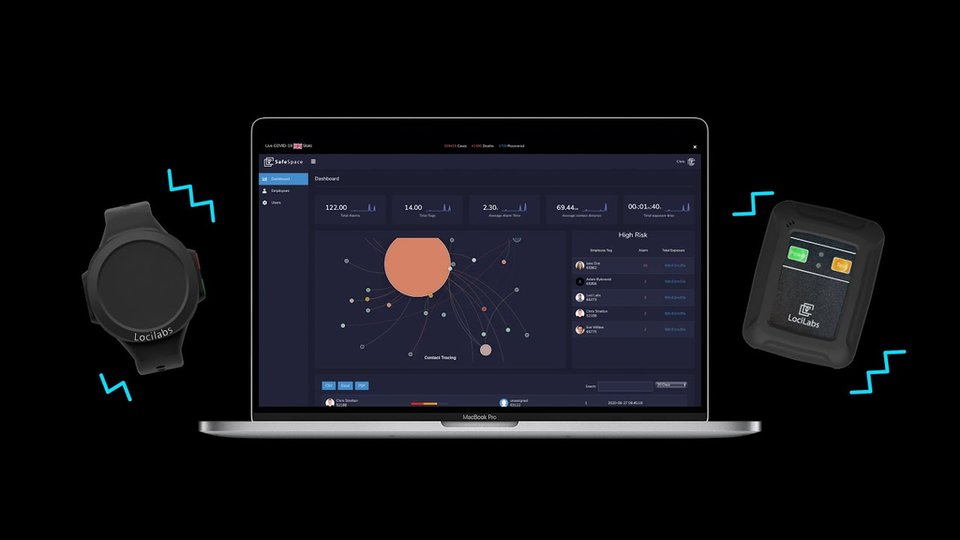

SafeSpace: social distancing for the workplace

UK tech companies DKN Capital and LociLabs have worked together to develop a wearable device to help people in the transport industry meet Covid-19 social distancing guidelines while they continue to build, maintain and repair critical infrastructure such as roadways.

The SafeSpace device, which comes in a watch form and a tag form to fix to a belt or hard hat, will issue real-time audible, visual and vibrating alerts if it detects another SafeSpace device within 6.5ft, slightly over the 6ft social distancing guideline. This is to ensure that employees are then able to maintain a safe social distance from each other while they work.

While the device is designed with the transport infrastructure workers in mind, the creators believe it could prove useful in virtually any industry.

TraceTogether Tokens: Singapore’s contact tracing tech

Singapore has turned to wearable devices called TraceTogether Tokens to compliment its pre-existing TraceTogether Covid-19 contact tracing app. All a person needs to do is keep the token on their person while out and about, exchanging Bluetooth signals with other TraceTogether Tokens or phones running the TraceTogether app nearby.

Device users will then be contacted by the Singaporean Ministry of Health (MOH) contact tracing team if they have been detected as having been in close contact with a confirmed Covid-19 patient.

The Tokens have been heralded as a great way for elderly people, who may not own sophisticated mobile phones, to be part of the country’s contact tracing scheme. They also have a battery life of six to nine months so that they don’t need any charging, while the app can drain a phone’s battery life fairly significantly.

The security features of iPhones also mean that TraceTogether has to be running in the foreground at all times for Bluetooth connections to occur, meaning Apple customers can’t use their phone for anything else if they want to use the app, making the Tokens more reliable for these users.

As with all contact tracing technology, the devices have sparked concerns about user privacy. In early June when the Token was first announced, there was public backlash against the government, a relatively rare occurrence in Singapore. An online petition was created calling for the devices to be scrapped, which at time of writing has over 54,000 signatures.

The MOH maintains that the device does nothing more than send Bluetooth signals to other Tokens or to TraceTogether app users. It does not contain any means by which to capture geolocation data, nor does it contain internet or cellular connectivity, so the encrypted data in the device can’t be remotely extracted from it my malicious third parties. The data is also erased after 25 days.

However, a user’s personal identity is still tied to the device. Apple and Google have also been involved in the development of contact tracing apps which alert users if they are at risk, but these do not reveal their identity to the authorities.

The MOH, on the other hand, can go from the Token’s encrypted ID straight to the individual it is registered to. Concerns have therefore been raised about the potential for the technology’s reach to escalate – a BBC article gave the example of fitting Bluetooth sensors to public spaces to identify Token users who are out and about when they should be self-isolating at home.

PULSE: open-sourced anti-face- touching tech

The PULSE device from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) may be able to do a lot to slow the spread of Covid-19, with very little. PULSE uses 3D-printed parts and affordable electronic components to remind the wearer not to touch their face.

Minimising how often you touch your face can have a significant impact on transmission risk when combined with measures like regular handwashing and mask-wearing, but can be more difficult to self-police effectively.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Worn as a pendant around the neck, PULSE uses a proximity sensor to vibrate when it detects that a person’s hand is approaching their face. The vibration becomes stronger the closer the hand gets, reminding the user not to touch their face unless they absolutely must.

A list of the parts, STL files and assembly instructions are all open-sourced and publicly available. NASA JPL has encouraged individuals and organisations to replicate, refine or enhance the PULSE design and make it available for general distribution and purchase.

Click the icons for more information

Oura: a smart ring to detect early Covid-19 symptoms

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), are using the Oura smart ring to test whether tracking data such as body temperature, heart rate and respiration may enable people to detect the early onset of Covid-19, before they notice they’re unwell.

The data collected by the Oura wearable will be combined with responses to daily symptom surveys, to build an algorithm that can help UCSF identify patterns of Covid-19 onset, progression and recovery. The research team are studying a group of more than 2,000 frontline healthcare workers as well as members of the general population.

Image: Oura

Doctors, nurses and other clinical staff who are in daily contact with sick patients who may have Covid-19 at UCSF campuses will receive Oura rings. The study is also open to all Oura ring users, who can likewise contribute to the data pool.

The Oura ring has a number of different sensors, including infrared LEDs, an accelerometer, gyroscope and three temperature sensors, which it can use to track various vital signs.

VitalPatch: monitoring Covid-19 patient drug response

In May, VitalConnect obtained Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its VitalPatch wearable biosensor, which can now be used to monitor heart-related side effects to drug treatments for Covid-19.

As different drugs are used to try and treat patients seriously afflicted by the disease, the VitalPatch biosensor can be used to detect changes in the patient’s QT interval, a measurement made on an electrocardiogram to assess some of the electrical properties of the heart.

Image: VitalConnect

Drugs such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, which have been used in attempts to treat Covid-19, can cause prolonged QT intervals for patients and may also lead to arrhythmias.

Using the VitalPatch, clinicians can remotely and continuously monitor the hearts of seriously ill patients to see if they are experiencing a prolonged QT interval as a result of their treatment. This can allow for the creation of more personalised and appropriate treatment plans.

The VitalPatch wearable can measure 11 physiological vitals overall, including temperature, heart rate and blood oxygen saturation levels.

SafeSpace: social distancing for the workplace

UK tech companies DKN Capital and LociLabs have worked together to develop a wearable device to help people in the transport industry meet Covid-19 social distancing guidelines while they continue to build, maintain and repair critical infrastructure like roadways.

The SafeSpace device, which comes in a watch form and a tag form to fix to a belt or hard hat, will issue real-time audible, visual and vibrating alerts if it detects another SafeSpace device within 6.5ft, slightly over the 6ft social distancing guideline. This is to ensure that employees are then able to maintain a safe social distance from each other while they work.

While the device is designed with the transport infrastructure workers in mind, the creators believe it could prove useful in virtually any industry.

TraceTogether Tokens: Singapore’s contact tracing tech

Singapore has turned to wearable devices called TraceTogether Tokens to compliment its pre-existing TraceTogether Covid-19 contact tracing app. All a person needs to do is keep the token on their person while out and about, exchanging Bluetooth signals with other TraceTogether Tokens or phones running the TraceTogether app nearby.

Device users will then be contacted by the Singaporean Ministry of Health (MOH) contact tracing team if they have been detected as having been in close contact with a confirmed Covid-19 patient.

The Tokens have been heralded as a great way for elderly people, who may not own sophisticated mobile phones, to be part of the country’s contact tracing scheme. They also have a battery life of six to nine months so that they don’t need any charging, while the app can drain a phone’s battery life fairly significantly.

The security features of iPhones also mean that TraceTogether has to be running in the foreground at all times for Bluetooth connections to occur, meaning Apple customers can’t use their phone for anything else if they want to use the app, making the Tokens more reliable for these users.

As with all contact tracing technology, the devices have sparked concerns about user privacy. In early June when the Token was first announced, there was public backlash against the government, a relatively rare occurrence in Singapore. An online petition was created calling for the devices to be scrapped, which at time of writing has over 54,000 signatures.

The MOH maintains that the device does nothing more than send Bluetooth signals to other Tokens or to TraceTogether app users. It does not contain any means by which to capture geolocation data, nor does it contain internet or cellular connectivity, so the encrypted data in the device can’t be remotely extracted from it my malicious third parties. The data is also erased after 25 days.

However, a user’s personal identity is still tied to the device. Apple and Google have also been involved in the development of contact tracing apps which alert users if they are at risk, but these do not reveal their identity to the authorities.

The MOH, on the other hand, can go from the Token’s encrypted ID straight to the individual it is registered to. Concerns have therefore been raised about the potential for the technology’s reach to escalate – a BBC article gave the example of fitting Bluetooth sensors to public spaces to identify Token users who are out and about when they should be self-isolating at home.

PULSE: open-sourced anti-face- touching tech

The PULSE device from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) may be able to do a lot to slow the spread of Covid-19, with very little. PULSE uses 3D-printed parts and affordable electronic components to remind the wearer not to touch their face.

Minimising how often you touch your face can have a significant impact on transmission risk when combined with measures like regular handwashing and mask-wearing, but can be more difficult to self-police effectively.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Worn as a pendant around the neck, PULSE uses a proximity sensor to vibrate when it detects that a person’s hand is approaching their face. The vibration becomes stronger the closer the hand gets, reminding the user not to touch their face unless they absolutely must.

A list of the parts, STL files and assembly instructions are all open-sourced and publicly available. NASA JPL has encouraged individuals and organisations to replicate, refine or enhance the PULSE design and make it available for general distribution and purchase.